The Cashman – a not very short story by Des Molloy

Billy Cashman wasn’t usually a man for deep reflection. He’d never been one for revelling in the past. The present was always enough for him … and he didn’t see that he had achieved anything of note to recall, so why go back?. He supposed that he was an easily contented person … a simple man. How he handled the present would always dictate how the future would unfold. Mostly it had been ‘more of the same’, the pathways easily identified and followed. He didn’t need further aspirations. He was happy with what he had. Billy loved the ‘travail’ of life, he loved the physicality and challenges of the outdoors … the relentlessness of remote station life. He’d never set out to be a jackaroo … or a ringer, but he was pretty ok with the mantle, one which was now possibly in doubt. Retirement could still be a few years away and the body was still ‘lean and mean’. But maybe change was in the air. Maybe it was time to find somewhere to settle … but where? He was happy where he was.

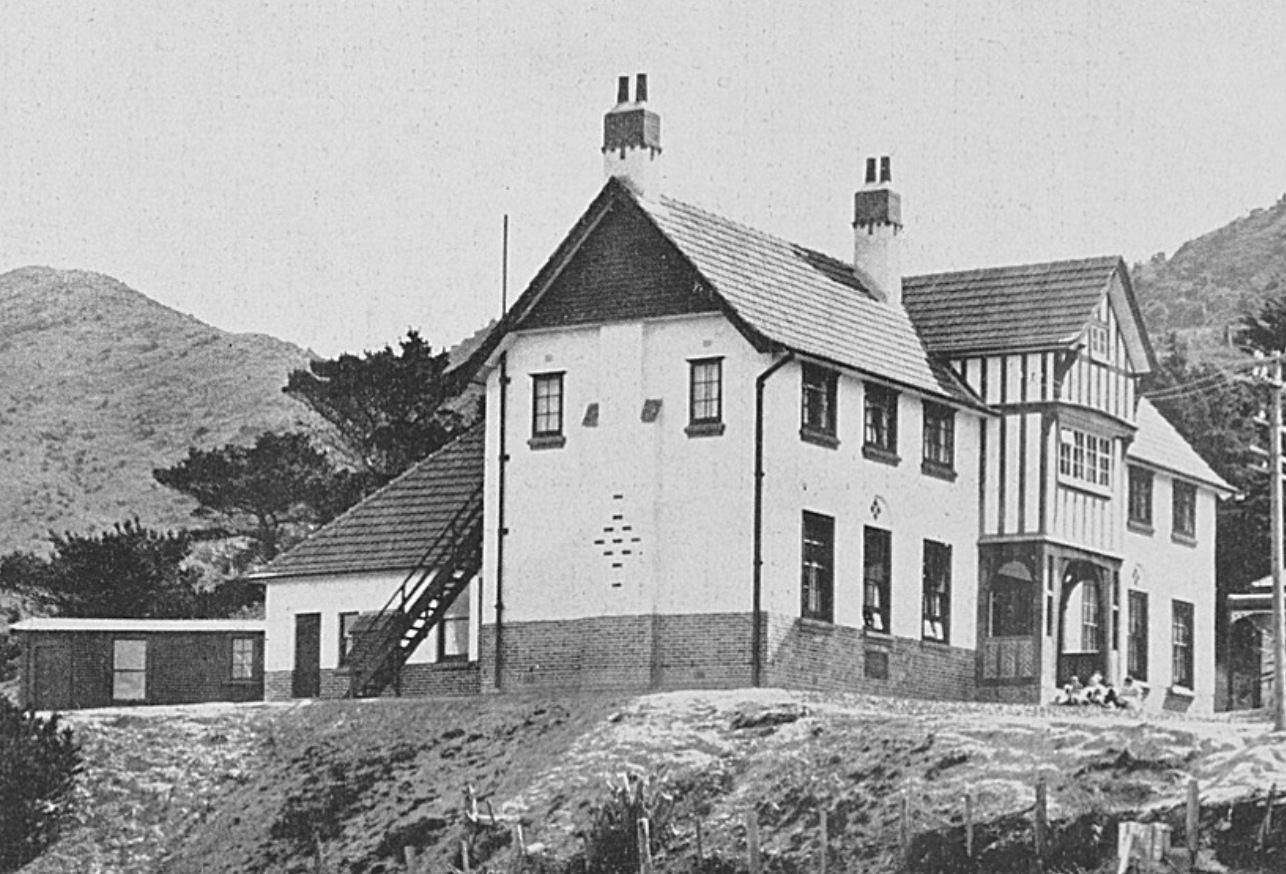

Looking back to the little boy growing up in Wellington’s Presbyterian Children’s Home in Berhampore, his first memories were of being part of a phalanx of children walking in step, down the long private driveway into Morton St and up the short hill to school. School was ok, but he always wondered about, and later envied, the freedoms of the other kids … the ‘normal’ ones. Billy’s world was one of controlment. There was the walk to and from school … and there were the grounds of the orphanage, and the foreboding two-storey WW1-era Boys Block. The on-site Girls' Block was off-limits, another place of mystery. Outings were only occasional and strictly orchestrated. Freedom was an alien concept … yet it was one he could glimpse. The orphanage sat slightly elevated, in a small gully backing onto a bush-clad hill. It was isolated, with no neighbours. High wire fences surrounded the grounds, allowing views of the outside … but no access. Billy remembers often looking across to what they called ‘the pines’ and further away to the left, below there was the rolling, lush golf course with Lilliputian figures playing an unimaginable game. Sometimes he would glimpse outside kids at the edge of the pines, spying on the orphanage. They looked to always be the same gang, as he could easily pick out one in particular because of his red hair. He knew they weren’t from school, so must be Catholics. He wished he could talk to them, but when he would go towards the wire, ‘Bluey’ and the others would melt away into the murky darkness of the pine forest.

Berhampore School gave way to South Wellington Intermediate, then Wellington High School … still known to most as ‘Tech’ reflecting its background as a blue-collar working class technical school focused more on preparing kids for ‘the trades’, rather than trying to compete in the world of academia. There was still no freedom to roam like the other kids did. The ‘norms’ had Monday tales of riding their bikes to Lyall Bay and beyond, and going down to the Thorndon Pool … because they could. Billy just had his imagination and the comfort of a series of books from the aged and limited orphanage library. Clearly the books had been gifted sometime back, as they were hardly modern. The adventures of Arthur Upfield’s half-caste aboriginal detective Napoleon ‘Bony’ Bonaparte took his mind away from his confinement, and gave him big horizons to dream of. The Aussie outback of Bony’s triumphs was a world he wanted.

Leaving age for both school and Church Care was 15 and it was a welcome milestone for the maturing Billy. He was uneasy about things he’d not seen, but he’d sensed at the orphanage. He wanted away. He was fortunate to have a teacher get him a job as a shepherd over in the South Wairarapa. This gave him all the space he craved. He was set off with $500 in a Post Office account that he’d never had access to before. The job was good, the fellow workers matey, the weekly outings to Martinborough an eye-opener. Although under-age, the pub was a magnet, and every Friday Billy would put his money in the jukebox and Janis Joplin’s ‘Bobby Magee’ would bombard the bar with “Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose! Nothin’ ain’t worth nothin’ … but its free!” The song was Billy’s anthem.

Billy loved learning the grown-ups’ skills of fencing and shearing, dagging, hunting, driving tractors, drilling and blasting, and operating a wide variety of equipment. He had an affinity for mechanical things … and nature. His licence endorsements filled the small dark-blue book in use at the time. All the while his Post Office account steadily accrued a healthy balance. Nothing frivolous was ever bought. Among his peers he was known to be on the parsimonious side. ‘Billy with the deep pockets and short arms.’ Billy found nothing in leisure as enjoyable as what was deemed ‘work’ in his new world. Opportunities for overtime were always taken up, and if ‘perkies’ were on offer, Billy was your man.

It was the pending requirement for passports, that nudged Billy into making the first definite step towards ‘Bony’s’ world. The Australian Minister for Immigration, decreed on April 24, that from 1st July 1981, Kiwis would no longer be exempt from needing one to travel across the Tasman. Billy had already decided that he didn’t want what he saw as bureaucratic intervention in his life. He’d endured an institutionalised upbringing and he hated the ‘control’. He wanted his world to be his world, with no interference. At the end of May Billy had withdrawn all his money from the Post Office, closed the account and booked a ticket to Melbourne. He was 19.

Melbourne was bigger and scarier than Billy had thought it would be, and he only managed a couple of days in a YMCA hostel before trolling through the classified sections of The Age looking for wheels. He needed mobility. It seemed a like a bit of serendipity was tagging along with him. The first listing in Cars and Vans for sale was ‘Austin Champ 4 x 4 and trailer – Outback Ready, $2,500’ Billy rang the number listed and made an arrangement to buy, subject to it being as advertised. It was located in Melton, an outer suburb, necessitating a train ride. This was exciting and all new to him. The owner met him at the station, telling him it was just a short walk to ‘home’. He was elderly but still with a spring in his step.

“Gidday son, I’m Lee Perrins, saucy, but not from the bottle!” Billy laughed, not quite sure he knew the reference, but he was drawn towards this old duffer and sensed a chuckle was appropriate.

“Do you know Austins? Maybe your mum and dad had one? Well, this one is different from any that they would have had! It’s a military one, like a Jeep!”

“Well no, I had no parents, but if it is suitable for the outback, I’m keen.”

Lee Perrins certainly could walk and talk. He was like an unstoppable gusher, and by the time they got to 17 Sunbelt Crescent, Billy felt he knew all there was to know about Austin Champs. They came about because after the Second World War, the British government created a Fighting Vehicles Research and Development Establishment (FVRDE) to modernise their land-based fast response capability. They got the Nuffield Organization (Owners of Morris, Riley, Wolseley, MG and Austin) to make three designs for testing. These were known as the Nuffield Gutty, and had enough identifiable flaws, that 30 improved prototypes were made, this time known as the Wolseley Mudlark. More improvements were made and finally a design was settled upon, and a contract was let for Austin to produce 15,000 Champs. These had an unusual, for the time, five-speed gearbox, and not one of the available Nuffield engines, but a four-cylinder 2.8 litre Rolls Royce product. The specification included independent suspension on all corners, and fully sealed engine and transmission units, so with the fitting of an included snorkel, they could wade through six-foot-deep water … and the ingress of dust into the working componentry was never a problem. The Australian Army ordered 500 immediately, and later a batch of second-hand ones. Ironically, because they were so good, they were expensive … and for the price, two and a half Landrovers could be bought. Being as they were still in times of austerity, the British Government subsequently did a backflip and terminated the order with still about 5,000 remaining to be supplied.

“We got ‘Champ’ when the Army auctioned them off in 1968, along with the half-ton ‘No 5’ military trailer. What a bargain, low mileage, always serviced! Over the years, me and Ngaio … she were a Kiwi too, we’ve done all the tracks and crossings. She’s gone now, so there is no reason for me to keep it all. I’ve been looking for a new custodian. It is fully kitted-out for desert crossings … sand mats, winch, water and fuel capability for 1,000 km. There’s a couple of swags and all the camping/cooking gear. I will throw in 1:100,000 maps of the whole country as well as some 1:25,000 ones of the Simpson Desert and the Canning Stock Route.”

There was no way Billy was going to turn down this opportunity. Champ was sturdy-looking and oozed a period charm … looking like he was from a war movie, still in the military green. A bit bigger and more rounded than a Jeep, there was a uniqueness about the whole rig. It looked the part, and was better than Billy had dreamed. Lee ended up hosting Billy for four days, teaching him how all the gear worked, showing him some of Ngaio’s best bush cooking, constantly talking and dispensing advice. For many this could have been annoying, but for Billy it was something to soak up, and take notice of. Billy thought of Lee as being something like he thought a dad would be … often irritating, but there to learn from.

“Head down to Leigh Creek in South Australia and ask at the roadhouse about the Oodnadatta, Birdsville and Strzelecki tracks … see what condition they are in and choose one. The Oodnadatta will take you west across to Marla on the Stuart Highway north to Alice. The other two head up to Birdsville and the Chanel Country. All good tracks that will be ideal for you to learn on, not much four-wheel-drive needed, and sooner or later people will come along if you are in trouble. There are big stations in that area always looking for jackaroos.”

Billy was so naïve and green, that he didn’t know that his bundle of Kiwi Dollars were not much use to Lee, and they’d need to get them changed for Aussie ones. It was at the Commonwealth Bank in Melton, that Billy made the decision that would define him and ultimately give rise to the legend of ‘Cashie the Cashman’. He declined the opportunity to open a bank account … he just handed over his entire life’s savings in Kiwi Dollars and took back a slightly less amount of the odd-looking Aussie notes. He suspected that it wouldn’t be a simple thing anyway to open an account. He had no passport, he had no birth certificate, his tattered driving licence included no photograph … he had no home address. The only person who knew who he was, was Billy himself … and that might not even be so, seeing that he was a foundling.

Back at Sunbelt Crescent, Lee showed him one more feature of his Champ, one he’d almost forgotten.

“I made these myself, to have a hidden safe place for our valuables when we travelled.” Below the rear seats, floor plates with Dzus quarter-turn fasteners gave access to two lockable strong boxes built into the space between the chassis rails. “They’re sealed by ‘O’ rings, so keep an eye out that you get everything aligned when you lock up. And like inside the Champ and the trailer, it is important that you pack for the corrugated roads … use lots of the foam stored in the side cabinet. You haven’t been shaken, till you do the corrugated outback roads. They’ll even shake the thoughts from your head, and the hair from your scalp … look at me!”

The 1,300 km to Leigh Creek was a bit tedious and Champ proved to not be very quick on the asphalted main roads, so three days were taken to get there. Billy was ok with this as each day showed him new things and by that third day quite a few Aussie icons were ticked off. Kangaroos, Wombats and Wedge-tail Eagles all noted, and the unmade roads definitely living up to Lee’s descriptions. The bull dust was a bit of a surprise and with Champ being an open buggy, he suffered a bit. There were some fabric sides and a canopy tucked away in the trailer but Billy preferred being ‘out there’. He loved also the Aussie swag, something he’d not seen before. Like a one-man canvas tent with a mesh bit of the hooped roof giving views of the night sky. He was living the dream.

Leigh Creek was small but bustling, with mining utes in evidence everywhere. It looked to be a town in the ‘now’. The roadhouse was not so busy and Billy was still pumping when a vision of the archetypal drover wandered across.

“Gidday mate! I’m Dean, more often known as Dingo. I see you’ve got Lee and Ngaio’s truck. Are you the new caretaker? Where are you off to? All the tracks are in good nick ahead no matter which you choose. You got time for a chat? If you have, you can pull over there with the road trains.”

This was more serendipity, as it turned out that Dean Fulton was the labour manager of Bill Brooks’ Cordilla Downs Station. Initially, he just wanted to check that Billy wasn’t making away with the Champ. Billy’s earnest manner and respectful references to Lee and his ways, soon had Dean onside and offering advice and later over a coffee … a possible job.

“I’m just on my way down to Port Augusta for a small skin cancer to be cut out, then I’ll be straight back. If you go on to Marree this afternoon, then tomorrow go up the Birdsville track to Mungarannie, stay there with old Bertie, Wednesday will get you to Birdsville itself. Thursday, unhook the trailer and go out to Big Red, the continent’s biggest sand dune, and have a play … get some experience in the desert, then Friday go on the Birdsville Developmental Road for about 100 km, then down our road which is marked Cordilla Downs Road. It is just on 90 km to the homestead. I’ll see you there about lunch time. I’ll be short-cutting up the Strzelecki, so will be back by then. If you impress the boss Bill Brook, we’ll take you on straight away. Bill’s a straight shooter. He came to ‘the Downs’ in 1918 as a ringer and now as an old man he has been able to buy the place and run 40,000 Herefords his way.”

Marree was little more than a railhead, but a great launching point for Billy’s introduction to the real outback. The five days spent getting to Cordilla Downs was an intense apprenticeship. Billy hadn’t known this level of solitude. There seemed to be no one out there in the intriguing wilderness, yet at each days’ end stop, there would be a scattering of battered 4 x 4s. There were sightings of numerous creatures that he didn’t know the names for. Foxes, dingoes and camels he knew, but the big lizards and the small rodent-like oddities and mini-kangaroos he didn’t. The sky seemed bluer that he’d ever seen, the horizons further away and the landmass predominantly red. All went well with the interview and Billy started a new life on the vast, million-acre-plus, outback station. The station was not far off straddling the South Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory borders and was in the Channel Country, an arid area of rivulets that mostly remain dry, then occasionally allow massive rainfalls in Far North Queensland to slowly meander a couple of thousand km down to Lake Eyre in South Australia. It was folklore among the indigenous Yandruwandha Yawarrawarrka people that a person would only see this flooding once in their lifetime, however since the 1970s it has seemingly become a once-a-decade occurrence with the waters sometimes taking two years to evaporate. It was in this crazy, harsh environment that Billy made his new life.

With the station being mainly stocked with cattle, there was lots of fencing maintenance as well as stock observations and care to do. The vast scale of the property meant that considerable time was spent away from the homestead, in either remote stone cottages or in his now preferred swag. Billy was just a bottom-of-the-pile jackaroo for the first couple of years, but he was quickly found to be a good learner and a competent all-rounder. Most importantly was the fact that he was steadfast. The zero-degree nights and 40 degree days were challenges that he relished. The emptiness of the country was something he marvelled at, and was content to remain in. He saw no need to make sorties away to Birdsville for a blow-out. The Federal government had a scheme for backpackers and the like who were seeking residency. If a three-month remote job was completed, the applicant moved towards the top of the queue for a visa. This saw a pretty constant supply of short-termers through Cordilla Downs. Mostly they were useless when it came to working, but often good company. Blily wasn’t a man of opinions, or odd behavioural traits, so got on well with those he worked among, as well as the management structure he interacted with.

All the while, the first of the strongboxes in Champ was being execrably filled. There was nothing to spend money on out where they were … and really, Billy couldn’t think of anywhere else he would like to be. A good observer, slowly he learned of his surroundings and came to identify the many desert animals, especially enjoying the oddities like the spinifex hopping mouse, the hairy footed dunnart and the bilby. Always uneasy around reptiles, he was ok with the goannas and bearded dragons but always wary of the desert python. All this, and a sky full of grasswrens, kites and kestrels made for an alien but enjoyable realm to be in. There was just the water-holding frog that evaded him for years. This unique species largely live under the ground only emerging to breed when the land gets soaked in a flooding. The annual rainfall of the area is only about 165 mm, less than a hand-span, so the water-holding frogs are not often seen.

Billy had always thought of himself as being an honourable sort, a follower of natural justice … with a good moral compass … not a breaker of rules … as long as they were just. He felt that the Presbyterian principles he was brought up under, were probably a bit too prescriptive, but he was more-or-less fine with the Ten Commandments. He felt it was reasonable to be required to sit tests to determine the competence of the applicant when it came to driver’s licenses and the operator tickets that he’d attained back in NZ. He supposed that after he’d been in Aussie for a couple of years, he was probably meant to pay somebody somewhere, some money to get an endorsement or another licence. He saw little need to do this, so didn’t. He possibly should have submitted annual tax returns, but didn’t … figuring that he didn’t really want to draw attention to himself … and the station took the government-required tax from his payments and forwarded it on, so he wasn’t ‘rooking’ anyone. What he did knowingly do during his fifth year at Cordilla … was dodge the mandatory five-yearly Census of Population and Housing. In the middle of June 1986, he told Dingo that he was finally going to take some of the leave owing him and that he would be away for about a month, possibly longer.

Whilst packing up Champ, Billy was surprised to hear a soft voice break into his focussed stashing of the necessities of the road. He was smilingly recalling Lee Perrins’ mantra of ‘a place for everything, and everything in its place’.

“So you’re going walkabout eh? OK if I ride shotgun?” Billy didn’t know Jedda, other than by repute. She was one of the Aboriginals who intermittently lived and worked on the station. He also knew that her father was named Napoleon Bonaparte, but none of the tribe had read the Arthur Upfield books … or even heard of Detective Bony.

“You don’t know where I am going!”

“Well I can see from your preparations that it won’t be Adelaide or Brisbane, probably not Mt Isa either. I feel that you are going my sort of places.”

It was only then that Billy noticed that Jedda had a battered old swag and was about to toss it into the back of Champ.

“You’re not running from anything?”

“No more than you! You won’t need a permit for the French Line or Colson Track across the Simpson Desert if I tag along My people are of some help sometimes.”

So began a pattern for Billy’s life going forward. Every five years he and Jedda went walkabout, usually being somewhere totally remote on Census night. That first jaunt had been a step up from Billy’s local adventures, truly into Jedda’s sort of places. They’d gone out to Birdsville, and topped up every tank they had with petrol, and then crossed the Simpson Desert via the afore-mentioned routes. Of course, Billy was soon pleased to have Jedda along. Not only was she an extra hand for the occasional extrication from soft bull dust holes and over sand dunes, but she was also a great cook and hunter-gatherer. What Billy enjoyed most, were the tales around the campfire or from their swags, looking up to the skies and Jedda explaining the stars’ roles in their lives. She’d learned the ways of the world from the elders and for Billy the stories of Dreamtime and the Rainbow Serpent, Narmarrkon, Lighting Man Gods and others, were intriguing, and as much based on reality as the imaginary invisible deity of his orphanage upbringing.

That first walkabout paused in Alice Springs, and it was outside Centralian Motors, the Holden dealership on Todd Street, that Billy had an opportunity to put in place a plan that had previously been just an embryonic idea from a Wheels magazine. Featured in the window was an immaculate 1972 Holden Torana GTR XU1. Billy recognised this as being the same as on the poster and in the dreams of a fellow shepherd back in New Zealand. The XU1 had also featured in a piece in Wheels magazine about ‘Cars to invest in’. Billy was a little surprised that the 14-year-old Holden was being offered for $5,000, which was $1,550 more than when it was new. The lurid but apparently standard ‘Strike-me-pink’ colour was certainly a bold statement, and in a moment of clarity, Billy could see that the wet-dream of a penniless teenage petrol-head, might indeed be the sort of thing they would pay top dollar for when they were 50.

“If I pay you cash right now, will you take $4,500? You can keep it on display for a while, as I will need to arrange transport.” Billy sensed only a moment of hesitancy before the archetypal car shark in his rumpled suit and shirt with a dirty collar, stuck out his hand and said “Done son … go get the moolah!” In a bizarre way, Billy had been enjoying taking from the strongbox, reversing the flow, and now here was an opportunity to nearly clean it out. ‘Call me Bob’ Downs’ eyes lit up when Billy came back ten minutes later and handed over the money in crisp notes. The paperwork was done in a flash and with a parting “Bob, If you find another one in mint condition, write to me!”, Billy and Jedda were on their way home no more than 30 minutes after first sighting this investment

The way home took them south on the tarseal to Marla, via a side trip out to Uluru and the Kata Tjuṯa dunes for a week. From Marla, the Oodnadatta Track was just an almost straight corrugated red-dirt road right across to Marree and Leigh Creek. They treated themselves to a night of comfort in the Marree Hotel before hitting the Strzelecki Track for the last couple of days back to the station.

“Six weeks and six thousand pingas, is pretty good, seeing that includes paying into my new private pension scheme!” Dingo was pleased to have him back and hear all his news. He was also quite excited about the XU1, and allocated an empty shed for it, noting that there was room for more. Four years later, Bob Downs came through with a 1970 model in the purplish ‘Plumdinger’ colour. Another ‘minter’, this time Billy had to pay $8,000, plus another $1,000 to get it back. Billy loved the availability of his pension. Unlike a figure in a passbook, he could just walk over to the big shed and lift the cover.

The Brook family management moved on a generation, but nothing much changed for Billy, he was now a ringer though, higher up the tree. They tried to get the workers to agree to their paying of wages directly into interest-bearing bank accounts, with just a bit of spending money handed over in cash. This wasn’t an option for Billy and he also saw little point in putting money into a bank maybe 1,000 km away. He’d rather have it in his strong boxes. As the years went by he’d become more and more vital to the running of the station. By the late ‘90s he had a good feel for everything that needed doing, what stock needed moving, what gear needed replacing, how to manage the staff. He’d become a key part of the continued success of the operation, which now operated organically alongside a couple of other stations in the area, also under the family ownership. It was a sophisticated business model with airfields and a company plane. Only Billy remained old school. They’d tried tempting him with the advantages of having a cheque book telling him how he’d be able to buy stuff without the risks involved in sending cash through the mail. Billy shrugged and refused. He knew what he knew and was happy that way.

The 1991 Census saw Billy and Jedda away across to what is known as FNQ and for Jedda, her first sight of the sea … and a crocodile, when they cut through the Daintree, en route to the York Peninsular. They enjoyed the ocean but strangely found the beaches quite linear. They missed the full 360-degree nature of the outback scenery. The bigger cities and towns they always found a little awkward, because they often sensed sniffy disapproval of their pairing. This negated any possible enjoyment in Townsville or Cairns. Strangely, the remoteness of Cooktown seemed to balance that out and they were accepted there and enjoyed a relaxing couple of weeks.

Over the years they explored the Gibson Desert, the Great and Little Sandy Deserts, the Great Victoria Desert, criss-crossing the country every time there was a Census to be avoided. Jedda was like a migratory bird. She came and went from Billy’s nest, often disappearing for weeks, but always returning, always warm and welcoming, sometimes with new wisdoms to impart. All the while Billy’s home-brewed pension scheme grew. He filled a 20’ container with motorbikes he chose that would sometime become classics. Nothing too old or vintage was sought. Billy wanted a sweet spot of 40 to 50 years when he sold. He’d read somewhere that, that was the optimum for returns … older and the connection is lost with the ‘lustees’. So it was that his collection included Kawasaki Z1s, Norton Commandos, LC Yamahas, Ducati Sports and SS 750s, a 951, a Moto Morini 350S, and probably the ‘jewel in the crown’, a MV Augusta America. Once the container was full, Billy moved on to gold, realising that it was much easier to store. At regular intervals the Brook family would bring back 500 g blocks when they returned from outings to the big smoke. The turn of the century came and went, Billy noting to Jedda that he’d been as many years in Australia as he lived in New Zealand.

When Billy left New Zealand, he had heard of computers but had never seen one. By the late 1980s the station used them. By the 2000s, there was the internet and cell phones. Billy was outside of all these advances, observing them with some disdain. Backpackers soon started to show Billy the ‘web’ on personal devices, which he could look at in awe, but not covet. These same temporary workers told of cards with access to their money. Billy chuckled inwardly thinking “Why?” His strongboxes were never far away. The levels within waxed and waned, but never went dry. He heard of personal IDs, but never sought to unravel the requirements and difficulties that he would face in getting one. He knew that driving on the public roads with only his old expired, photo-less Kiwi Driver’s licence was a risk, and that he’d he up for a $200 fine if he was caught. He figured that where he roamed the odds were pretty good.

The learnings from their many desert crossings, gave them confidence in 2021 to aspire to take on one of Australia’s ultimate ‘outback challenges … the Canning Stock Route. This would probably be their last big adventure in Champ. After the by-now familiar Simpson crossing and re-provisioning in Alice Springs, the pair crossed the Tanami Desert to Halls Creek in the Northern Territory. Here they paused for a couple of days and gave Champ a full service, changing the oil and filters as well as thoroughly checking every nut and bolt. Lee Perrins’ meticulous custodianship for more than 20 years was evident in many ways. He had lock-wired all crucial nuts … just like a race team did. This ‘extra mile’ was now showing up. Champ was proving to be every bit as able as the newer Land Cruisers and Safaris they had encountered. The Canning Stock Route was not far off 2,000 km long with only one fuelling point. There were 900 sand dunes to cross and the indigenous owners, the Kuju Wangka (One Voice) encouraged the adventurers crossing their land to do so without trailers. This meant quite a different plan of attack, more intense packing, and as advised they buddied up with others. The trip was ultimately a success and companionably enjoyable. However on later reflection once home, Jedda and Billy acknowledged that they preferred the total solitude of their company and own adventures … they didn’t need to be ticking off a bucket list with a group of weekend warriors.

The time was approaching for Billy to decide on an exit plan, the future was closing in on him. Dingo had retired and moved up to Boulia, although that hadn’t worked out well for him, as he passed away less than two years after leaving Cordilla. Billy moved up yet another notch on the station’s organogram, but soon realised that this involved more paperwork … which actually meant less, because electronic devices were now recording everything and Billy didn’t have a natural affinity for these. He was a dinosaur whose time had passed. Maybe, it was time to cash in his pension and find somewhere to live out his remaining years? He’d already tested the water in 2023 with the Plumdinger XU1 pleasingly fetching $150,000. The downside was the difficulty in getting paid in cash. The Federal Proceeds of Crime Act had led to restrictions on how much cash a person could withdraw from a bank at any one time, and also how much cash they could deposit. Cash was no longer king. Billy now learnt that there now were less banks than he remembered. Society had evolved, and people used hole-in-the-wall machines to get money, when and if they needed any … which was increasingly less often. Some banks’ machines would only allow $1,000 per day per person to be dispensed, and even the generous ones, only $2,500. It seemed that the only habitués of the cash world were criminals … drug dealers! Larger amounts could only be arranged ahead of time from specific banks with strict ID analysis and multiple questions. Buyers seemed to think that a cash cheque was the same … well it wasn’t to Billy. He meant to live the rest of his life from a stash of bank notes. Ultimately Billy did get his cash, some of which he turned into gold.

The container of bikes was disposed of all in one go. After much angst, Billy had agreed to having an agent sell the lot at Melbourne’s 2024 Motors and Masterpieces event. The MV Augusta America sale price blew him away a little as it fetched $145,000. Billy had bought it in 1987 subsequent to the stock market crash for $17,000. One of his Ducatis also fetched good money … $73,000, whilst the Z1s and Norton Commandos brought in low $20,000s. The LC Yamahas were a bit disappointing but all up, Billy’s pension fund swelled by just a little shy of $300,000. He arranged that the agent transferred those funds to his preferred gold dealer in Mt Isa. When Billy bought his first 500 g bar of gold in 1994, it cost him $6,250. In 2024 he was selling back to the same dealer for $81,000.

Back at Cordilla Downs Billy did a tote up. He still had the Strike-me-pink XU1 which he was confident was now worth $175,000, he had a little over $100,000 in bank notes in the strong box, along with three kilos of gold worth $450,000 plus. And now he had another $285,000 in bars up in Mt Isa. So he figured that he had over a million bucks to his name, which he reckoned was pretty good for an orphan from Berhampore. Possibly no better than a city boy paying off a mortgage in Adelaide, but it should be enough to get him to the end, he figured … and hopefully the gold value would continue to grow faster than he used up the bank notes.

And then the Eureka moment! About 45 km from the homestead was Billy’s favourite old stone stockman’s cottage. It was pretty crude but for some reason it had always provided Billy with tranquil nights. It was slightly raised, giving good views across the wilderness. It was usually used as a camp on the way to or from one of the boundary fences and Well 57, but more and more of the station’s observational work was being done by drones operated from the homestead. This had led the cottage to be more or less unused. Billy put a proposal to the Brook family. He would work in his current role until his 65th birthday in May 2027. He would then work for free, two days a week, or 90 days a year, in whatever role the family directed, and in return he would have a lease free of charge on the cottage until his passing. If he was able, willing and wanted by the family on more than the two days a week, he was to be paid commensurate with the role and tasks at hand.

“Hell yes!” said the family

… and I’ve always wanted to end a story with … and he lived happily ever after!

*The manager of the Morton St orphanage, Wally Lake was considered a pillar of society, being awarded an OBE in 1986. However, he was subsequently exposed as ‘The Beast of Berhampore’ and Police were poised to charge him with a long string of child sex offences when he died in 2004. The orphanage was burnt down by a resident in 1989.

And yes, I was that ginger-haired kid at the edge of the pines.

Presbyterian Children’s Home in Morton St, Berhampore, Wellington, NZ

Austin Champ

Holden Torana GTR XU1

MV Augusta 750S America

What better way to show your support than shouting me a cuppa. Better yet, let’s make it a pint!

Sounds great, tell me moreNo Winners – an exciting piece of escapism from Bryan (Nod) Wilson

Read this Short StoryHappiness is the mid-point between too much wealth and not enough.

Read this Short StoryNo trait is more justified than revenge in the right time and place. Meir Kahane

Read this Short StoryFrom marking time to a possible new beginning

Read this Short StoryAs he strode up through the mall, Rick Dernley felt happy with his lot in life.

Read this Short Story